Peranakan Culture, The Nyonya Kebaya and Ethnocentrism

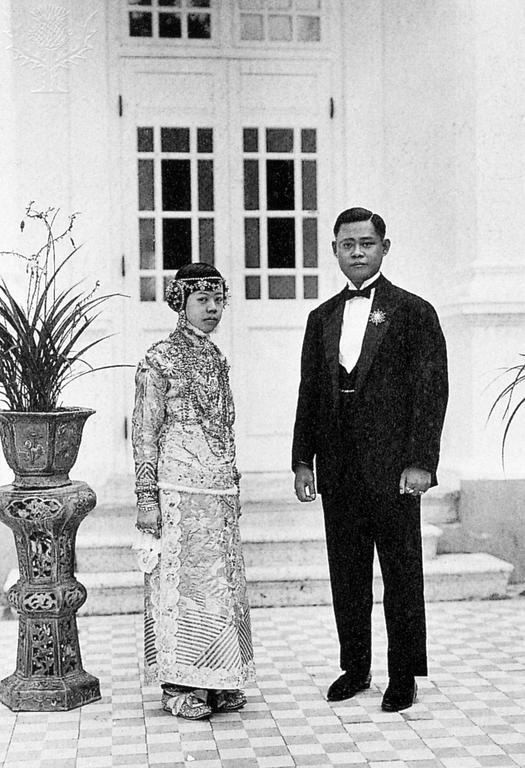

Fig 1. A Peranakan bride and groom pose for their wedding photograph, Penang (1925)

Introduction

Peranakan culture has always been a symbolism of pride for Southeast Asia, especially Singapore. However, while its antique grandeur, timeless style and materiality are celebrated by Southeast Asians, there are multiple complexities that elucidate a cultural phenomenon that goes overlooked, or even forgotten. As globalisation progresses, the desire for modernity becomes more prevalent. Henceforth, a gradual decline of future Southeast Asian generations knowing about the traditions and heritage of Peranakan culture is imminent. It is no doubt that some Southeast Asians do take pride in our Peranakan history, however without knowing the full cultural context and ramifications of what makes a Peranakan, Peranakan. Growing up in an ever-evolving modern Singapore, I was never exposed to my ancestry. It was only when I was in my last year of kindergarten, where I chanced upon The Little Nyonya (2008), a Singapore fictional TV drama series based on true events of Singapore’s past (Figure 2). The drama talks about the life of a girl, renowned Chinese Singaporean actress Jeanette Aw, spanning two generations, featuring crucial historical moments like the Japanese invasion of Singapore in WWII and an accurate portrayal of life with the Straits Chinese. As a Southeast Asian Chinese born Singaporean, with Peranakan ancestors spanning across the Malay-Chinese peninsula and the Straits of Melaka—the Chinese Coolies and Towkays, the Pua-Tangs and the Baba Nyonyas, with present Singapore being racially-diverse yet due to our strict political censorship and condonement of any political free speech, has transgressed societally into an ever-stagnant ethnocentric nation—learning about what it means to grow up alongside my peers whose daily routines were affected by Chinese privilege, my goal is to educate audiences on the true culture of being a Peranakan—what it means and what it can mean, and that it should be understood and appreciated fully with the praxistical theory of its past and future becoming, in order for it to evolve concurrently at its utmost cultural potential. I will briefly run through its cultural history, the possibility of cultural vanish, the material culture of the Nyonya Kebaya and Peranakan culture’s overlooked ethnocentrism.

Figure 2. Scenes from The Little Nyonya TV series (2008)

Peranakan Origins

The term ‘Peranakan’ has always been around, but growing up in Singapore, people never truly labelled themselves as it. Eventually, the term became used more as a successful tourism strategy instead of an identity. For example, Singapore Airlines, statistically known as the world’s best, campaigned the iconic cabin crew with the Kebaya (Figure 4) and the famous Peranakan-style shophouses preserved all over Singapore (Figure 5). Most Singaporeans who were born native have ‘Peranakan’ ancestors, however, many have undergone assimilation be it forced or voluntarily and have happily embraced the unique cultural identity as neither Chinese nor Sumatran, but a bit of everything and everywhere, in between (Lokman).

Fig 3. The Ugly Truth of the 21st Peranakan Trend (2023)

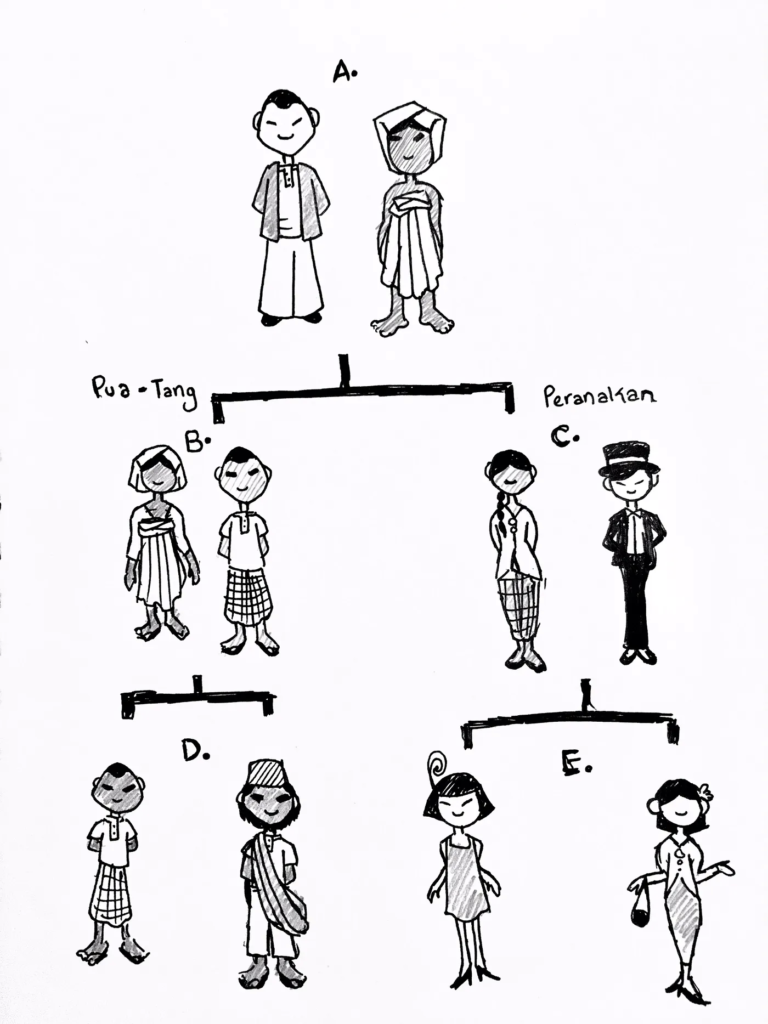

According to the National Library Board of Singapore, Peranakan generally refers to a person of mixed Chinese and Malay/Indonesian heritage with its cultural influences known as a hybridity of Chinese, Malay, Indonesian and Western. Many Singaporeans trace their origins to 15th century Melaka, now known as Malacca, where Chinese traders (Chinese Coolies) back then married local indigenous Southeast Asian women (Figure 3). Peranakan men were known as Baba, while the women were known as Nyonya. Peranakans were also known as the Straits Chinese, and as generations passed, many have assimilated into larger Chinese communities. While the origins of Singaporean’s Peranakan Chinese are hard to pin down, scholars believe that the Straits Chinese were born during the British-controlled Straits Settlement in Singapore, Penang and Malacca, where they were entrepreneurial merchants and traders fluent in English. During the British colonial period, these Straits Chinese were regarded as King’s Chinese in reference to their status as British subjects, many of them appointed as community or civic leaders (Figure 6).

Fig 4. A Set of Blue Kebaya Belonging to Singapore Airlines

Fig 5. Peranakan Shophouses, Koon Seng Road/Joo Chiat (2020)

Fig 6. The early members of SCBA (Straits Chinese British Association) in the 1900s (2013)

Vanishing Culture and the Significance of the Nyonya Kebaya

From the 15th century all the way to the 1900s, Peranakan culture thrived. With its delectable cuisine, intricate beadwork and embroidery, the Peranakans were seen as no less than wealthy. Interracial marriages were at its peak, and the traditional costume for Peranakan women became the Nyonya Kebaya, gradually replacing the Baju Panjang (Malay long dress) in the 1920s as the new material culture and standard modern fashion for Peranakan women (Figure 7 and 8). Compared to the Baju, the Nyonya Kebaya is a mixture of the Malay Baju and the Chinese Cheongsam, incorporating a tighter-fitting sheer embroidered blouse that is paired with the Batik Sarong. Made from voile, a sheer fabric that comes in multiple shades and often decorated with embroidered motifs such as sulam. Popular sulam motifs depicted include flowers, butterflies, phoenix, insects and even people—usually telling a story or recreating an intricate artwork. Semi-transparent, the Nyonya Kebaya is worn with a camisole and secured at the front by three interlinked handmade brooches.

Fig 7. Peranakan bride and groom, the bride wearing a Baju Shanghai, Penang, early-mid 20th century (2 June 2022)

Fig 8. Malaysia-Singapore: Nyonya women wearing sarong kebaya dress typical of the Peranakan Straits Chinese community (c. 1950)

However, with its short three-generation run, the rubber crash in the 1930s and the Second World War proved the continuity of the Peranakan culture to become obsolete (Mahmood, 2003). For example, the sulam embroidery top was originally done by hand, however, as what we expect from the emergence of mass production technologies, the cottage embroidery began to decline by the 1970s and only a few remaining elderly nyonyas in the present still wore their authentic kebayas with matching sarongs daily, while the generation below capitulated to modernisation. The focus on efficiency for Southeast Asia through modernisation subfactors—technological advancement, shifting values on collectivism, a transgressive shift that further encapsulates notions of imperialism from Western regimes, has resulted in less emphasis on manual craftsmanship, performative dinner rituals and grandeur weddings—a commodity during the Peranakan period. The rising emphasis on tourism for Southeast Asia’s economy posits an exploitation of Baba Nyonya enclaves, where items are seen by the public as attractions—redeveloped into items of functionality and aesthetic, rather than items of value, historical preservation, a tangible remembrance of heritage. The absence of creolised awareness—the reunification of material items like the Nyonya Kebaya, alongside the Peranakan culture, has been made sedentary.

However, the further push of the paradox is made possible—due to its timeless appeal, the preservation and upkeep of this traditional garment although less informed in the present, is still being earnestly preserved—many elderly still keep their ancestors’ kebayas where they pass it down as family heirloom to future generations (Figure 9). The retainment pays homage to keeping its ethnic identity alive; preventing the possibility of cultural extinction, raising global recognition and proof of existence. This cultural amalgamation fosters common sense of belonging, a step further towards the unfolding of nuanced colonial narratives in Southeast Asia’s history and a deeper understanding of timeless feminism in the radar of the Nyonya Kebaya. With the knowledge of this, a heterogeneous catalyst could be evolved as passed down current generations maintain their heritage while evolving their culture, integrating it into different aspects of one’s ethnic identity—fashion, education, values and livelihood. The duality embraces modernism, reinforces Malaysia, Singapore and Indonesia’s kinship and multicultural strength—foreshadows symbolism of racial unity and interconnectedness.

Fig 9. The Nyonya Kebaya: A Century of Straits Chinese Costume (2004)

The rarity and disappearance of the Nyonya Kebaya due to modernisation and desire for efficiency resulted in its evolution to just the regular, more functional and versatile Kebaya, heavily favouring embroidered lace, a batik sarong skirt—tight fit and a slit in front, plain or a wrap-around (Figure 10).

Fig 10. Modern Kebaya (2024)

Ethnocentrism: Is Peranakan a Phenomenon of Multiculturalism or Exclusivity?

It is no doubt that the idea of Peranakan posits racial hybridity, however, cultural intellectuals can argue that the term Peranakan can in fact be the latter. Due to the way Peranakan culture has been portrayed in modern Singapore, a tourism scheme with little to no concurrent representations in the present—a sense of distraction to the real cultural nuances, it could easily be seen as a beacon of racial harmony. However, it is perceived as a hoax by many Southeast Asian cultural intellectuals—a stereotype more than anything else. What the current trend refuses to represent is the complex multiculturalism of Peranakan—the true Peranakan man is heterogeneous. However, the idea of The Peranakan Man is usually associated, historically, with the rich who have more Chinese blood than they do Malay/Indonesian, when in fact, it should be much of the latter. As seen in a simple diagram of Figure 4, ‘Peranakans’ would never exist if it were not for local indigenous people that embodied ethnic Southeast Asian cultures which is contradictory to what a Peranakan should be seen as. Back in the day, many would argue that you need to have more ‘Chineseness’ in you to be deemed suitable and ‘enough’ to be labelled a Peranakan—a way to create the purest Chinese descendants. The free and wealthy few Peranakan, instead of being a representation of cultural inclusivity, is actually an enigmatic elitist term that encourages ethnocentrism. As a sense of status, these men would look for a mixed Chinese woman instead of what they called an ‘indigenous slave’. These Chinese women were simply raised to cook Peranakan cuisine, bake, sew and be a wife that could give many Straits Chinese men Chinese children, especially boys that could pass down the Chinese family name. It started to fit a certain subgroup of people that were simply trying to reduce ‘non-Chinese’ blood in the family. Referencing The Little Nyonya (2008) in Figure 2, the local film company, Mediacorp who made the series, casted only Singaporean Chinese or East Asian actors, barely a single ethnic Malay or Indonesian cast was represented to the Singapore public.

In addition, one can argue that the evolution of the traditional Malay Baju into the Nyonya Kebaya garment is likely a racial commodity of Chinese superiority instead of the affairs of cultural amalgamation and unity. This pedagogy often goes overlooked by Singaporeans, choosing to acknowledge cultural modification of Peranakan fashion ‘progressive’ and ‘appealing’ tourism, money-pulling side, instead of recognising its controversiality. Although not proven, the severity of this cultural enigma is a more than enough factor to debate this as a likely probable cause, or even, a factor that contributed to Chinese superiority. This internalised racial segregation has since then transcended into the present—the ones deemed a true Peranakan are essentially Straits Chinese who could only trace their multicultural heritage from their ancestors. Chinese privilege in Singapore is still a present prevalent issue that has yet to be fully recognised by majority Chinese Singaporeans, with a majority of the Malay, Indonesian and Indian Singaporeans feeling a sense of subtle ‘less than’ in terms of basic rights, living standards, linguistic inequalities and even political authoritarianism.

The practice of colonialism has a main part to play. As seen in Figure 6, the British intrusion into this cultural amalgamation has resulted in a clear ethnic division, where the Straits Chinese were more favoured compared to the native Pua-Tangs. Many of these ‘Kings’ Chinese’ men were appointed as community and civic leaders, garnering a higher stature, causing clear racial segregation during the 1930s in Singapore. The sense of proximity to whiteness through colonial manipulation created far more complex of a cultural enigma—subtly, further oppressing the native’s cultural positionality, placing them on a lower pedestal in terms of political authoritarian matters, ability to contribute to the economy and basic living standards. The Chinese on the other hand, took no hesitation through being favoured due to the political and economic opportunities favoured to them by the British subjects—this enigma has transcended to the present.

It is no doubt that the Straits Chinese people is still a symbolism of the infamous Peranakan culture, but what one must not forget is the visibility of racialisation that comes with it, its long-embedded ethnocentrism which has transgressed present Singapore, along with role of the British colonies in it, who heavily promoted the Straits Chinese during colonial times. Singapore, apart from its metropolistic modernisation, was ultimately still a trading port native to the indigenous Malays (Pua-Tangs), Indonesians (Sumatrans), who inhabited native Singapura at its purest form, before the involvement of Stamford Raffles and his colonies, and even the Chinese immigrants (Chinese Coolies) who came looking for work.

Conclusion

While efforts of Peranakan preservation, especially with the famous Nyonya Kebaya are concurrent, celebrated and advertised throughout Southeast Asia, it is essential for the true Singaporean to acknowledge its deeply-embedded ethnocentrism that has innately transcended to the present, in order to educate future generations. What feels wrong about present Peranakan-ism is its subtle neoliberalism notions—it is presently perceived for its historical/nostalgic tone, a function for monetarism as if true multiculturalism is only acceptable in history and not something in the present, if one ignores its internalised ethnocentrism. For example, most items that are labelled Peranakan are in fact, not exclusive to that culture but instead an amalgamation and reunification of other cultures—that is what true Southeast Asia racial unification is about. And as what stereotype implies—Singaporeans, with their efficiency to progress further in a capitalistic corporate notion (something our respected former Prime Minister, Lee Kuan Yew strategically embedded into Singaporean culture for us to thrive as the richest country in Southeast Asia, or quite in fact, the world), it is easily understandable why one, especially a current Chinese-born Singaporean can have a subtle sense of lackluster, ignorant attitude of this past enigma, as what we call the attitude of Chinese Privilege. In addition, the role the Peranakans had with the colonial institutions, the exploration of this paradigm can unfortunately contribute to the insinuation of further colonial misrepresentations of exploitations which could lessen anticipatory attempts to bring forth Peranakan culture to the western regimes. Henceforth, as a Chinese-born Singaporean born with this internalised privilege which took me years to uncover (through my Malay, Indian and Indonesian peers), my goal is that Singaporeans currently work to reinvent what Peranakan culture is, whether through non-institutionalised curatorial projects and exhibits, forums for discussions, or even just simple heart-to-heart education, individually and collectively. This creolised paradigm of reinvention and recreation, without modifying anything authentic to the innate beauty of Peranakan, bringing about its idiosyncratic characteristics, will be proven crucial for the rebirth of essential Singaporean Peranakan culture in present Southeast Asia, preventing the further internalised transgression of our racial morality, that is the Chinese privilege, and not relying solely on monetary means for capitalist purposes, nostalgia of contested Peranakan material, objects and art, exploited historical pedagogies of other native culture crucial for Peranakan culture to exist. This deconstruction hence proves for Peranakan culture to thrive and be seen at a better, more dignifiable de-exclusive positioning, paving a way for further de-ethnocentric globalisation and cultural recognition and appreciation for the natives, indigenous and even immigrants—bringing out true racial harmony.

Bibliography

Mahmood, D. (2004) The Nyonya Kebaya: A Century of Straits Chinese Costume. 1st edn. Singapore: Tuttle Publishing.

National Heritage Board and The Fashion Design Society (1993) Costumes Through Time, Singapore. 1st edn. Singapore: National Heritage Board and The Fashion Design Society.

Hall, S. (1990), ‘Cultural Identity and Diaspora’ in Gilroy. P and Gilmore, R.W. (Eds.) Stuart Hall: Selected Writings on Race and Difference, 2021. Duke University Press.

Said, E.W. (2014 [1979]) ‘Knowing the Oriental’, in Orientalism. New York: Vintage, pp.52-71.

Bovy, P. M. (2017), ‘The Perils of “Privilege”: Why Injustice Can’t Be Solved by Accusing of Advantage’. 1st edn. St. Martin’s Publishing Group.

References

1. Cheong, S. (2016) A Vanishing Culture — The Intricate World of the Peranakan. Available at: https://www.throughouthistory.com/?p=3547

Accessed: 25 October 2024.

2. Soon, LW. (2023) Nyonya Kebaya — A Timeless Symbol of Racial Unity. Available at: https://www.bernama.com/en/bfokus/news.php?leisure&id=2217324

Accessed: 25 October 2024.

3. Faire Belle. (2024). The Significance of Nyonya Outfits in Peranakan Culture. Available at: https://www.fairebelle.com/blog/the-significance-of-nyonya-outfits-in-peranakan-culture?srsltid=AfmBOoo5tfJEuXrVBhNR6uhLCUIVNphgZaqvthMEKGapf__uKZy91ACc

Accessed: 25 October 2024.

4. Li, O.L. (2019) The Lost Culture of the Beautiful Kebaya. Available at: https://espoletta.com/2019/12/11/the-lost-culture-of-the-beautiful-kebaya/

Accessed: 25 October 2024.

5. Ong, J. (2024) The Nyonya that Symbolises Our Cultural Fusion — Nurul Huda Hamzah and Lim Ghee Seong. Available at: https://malaysia.news.yahoo.com/nyonya-symbolises-cultural-fusion-nurul-012750653.html?guccounter=1&guce_referrer=aHR0cHM6Ly93d3cuZ29vZ2xlLmNvbS8&guce_referrer_sig=AQAAANJYiHwJiVY_WYvymlIyzEAwt3YwzuNyFP6uV40fmBYQbKIgr7Ab4MbM0DckuR724UvqK2ZoqSWYx9Gfn57kEyk_igBSUbadmJ-0pUPtOLQflXlD2LwyGbFMnO08bjTDcpQJJ6-FPJebrQKXZR-8tk6Ba9JHn7k2ORdlJCJCeuGT

Accessed: 7 November 2024.

6. Lokman, B. (2023) The Ugly Truth of 21st Century Peranakan Trend. Available at: https://medium.com/@bernardlokman/the-ugly-truth-of-21st-century-peranakan-trend-d5b047bedff3

Accessed: 10 December 2024.

Images

Fig 1. Britannica ImageQuest, Encyclopædia Britannica. (Jun 02 2022) A Peranakan bride and groom pose for their wedding photograph, Penang, c. 1925 [photograph] Available at: quest.eb.com/images/325_4376112. Accessed 25 Dec 2024.

Fig 2. Mediacorp. (2008) The Little Nyonya TV Series [Film, still]

Fig 3. Lokman, Bernard. Medium. (2023) The Ugly Truth of the 21st Peranakan Trend [illustration]

Fig 4. WLGWH Shop. A Set of Blue Kebaya Belonging to SIA [photograph]

Fig 5. SG Shophouse. (2020) Peranakan Shophouses, Koon Seng Road/Joo Chiat [photograph]

Fig 6. Song, Ong Siang. (2013) One Hundred Years’ History of the Chinese in Singapore. London: John Murray [photograph]

Fig 7. Britannica ImageQuest, Encyclopædia Britannica. (2 June 2022) Peranakan bride and groom, the bride wearing a baju Shanghai, Penang, early-mid 20th century [photograph] Available at:

quest.eb.com/images/325_4375703

Accessed: 21 Dec 2024.

Fig 8. History/Universal Images Group. (1950) Malaysia-Singapore: Nyonya women wearing sarong kebaya dress typical of the Peranakan Straits Chinese community [photograph] Available at: https://quest.eb.com/images/search/nyonya/detail/325_4383480

Accessed: 23 Oct 2024.

Fig 9. Mahmood, Datin Seri Endon. (2004) The Nyonya Kebaya: A Century of Straits Chinese Costume [photograph] Available at:

Accessed: 23 Oct 2024.

Fig 10. Kiara Official. (2024) Dahlia – Gold Modern Kebaya [photograph] Available at:

Accessed: 23 Oct 2024.

Leave a Reply